The Clash’s Reggae Revolution Examined. Just two years into the Seventies British punk era, this is no three-chord thrash. A brave, culturally and politically insightful brilliant record that asked questions the scene wasn’t ready to answer.

Many years on from its release, Joe Strummer and Mick Jones’ most pointed cultural critique still cuts like a razor through the pretensions of punk’s supposed solidarity. ‘Seventy Eight’s “White Man In Hammersmith Palais” wasn’t just The Clash dipping their toes into reggae waters, it was a full-blooded dive into the contradictions of being white, privately educated (or art school) punks singing about revolution whilst signed to a major label.

The genesis of this track lies in Strummer and Don Letts’ pilgrimage to see Jamaican acts like Dillinger, Leroy Smart, and Delroy Wilson (the ‘Smooth Operator’) at the famous West London venue in early 1978. What they witnessed wasn’t the cultural communion Strummer expected, but a stark reminder of his own position as an outsider looking in. The resulting song became punk’s most honest examination of cultural tourism and political posturing.

Musically, it’s The Clash at their most adventurous pre-London Calling. The always under appreciated Topper Headon’s ska beat is perfect, not a ham-fisted attempt but a genuine understanding of reggae’s rhythmic subtleties. Mick Jones’ guitar work walks the tightrope between punk urgency and reggae’s more spacious approach, whilst Simonon’s bass provides the crucial foundation that makes the whole thing swing rather than simply thrash.

But it’s Strummer’s lyrical dissection of the disappointment of that night in the lightweight way the bands presented – plus the culture clash South London zeitgeist that elevates this from mere genre experiment to the essential punk document it has become. His observations about fashion victims “too busy fighting for a good place under the lighting’ and weekend revolutionaries were aimed squarely at punk’s emerging orthodoxies and not for the first time. That fabulous line about ‘turning rebellion into money’ and the hollowness of sloganeering hit closer to home than many wanted to admit. This wasn’t The Clash having a go at the establishment this was them turning the mirror on themselves and their scene, one now infiltrated by the Far Right.

The single’s commercial failure at the time, it barely scraped in, seems almost inevitable in hindsight. A huge fork in the road that was too reggae for the punk purists, too punk for the Rastas, and too uncomfortable for those who preferred their politics less complicated including anti-violence, wealth distribution, unity. Lyrically Strummer is really kicking off. Radio programmers didn’t know what to do with it, and neither did much of the press initially. This ain’t no White Riot redux.

Urban mythology has built up around the track over the years. Some claim Strummer wrote it in a fit of disgust after seeing Far Right punks and skinheads doing Nazi salutes at the Palais gig, though those who were there aren’t convinced of that. Others insist it was a direct response to criticism from Jamaican musicians about white bands appropriating reggae. The truth, as usual, is probably more mundane: four young men trying to make sense of their place in a musical and political landscape that was shifting beneath their feet.

What’s undeniable is the track’s influence on what followed. Without “White Man,” there’s no London Calling album, no “Rudie Can’t Fail,” no bridging of punk and reggae under the influence of Letts’, and that became one of The Clash’s defining characteristics. It opened doors not just for The Clash but forother bands who realised that punk’s year zero mentality was creative suicide and a punky reggae party might be route one for them too.

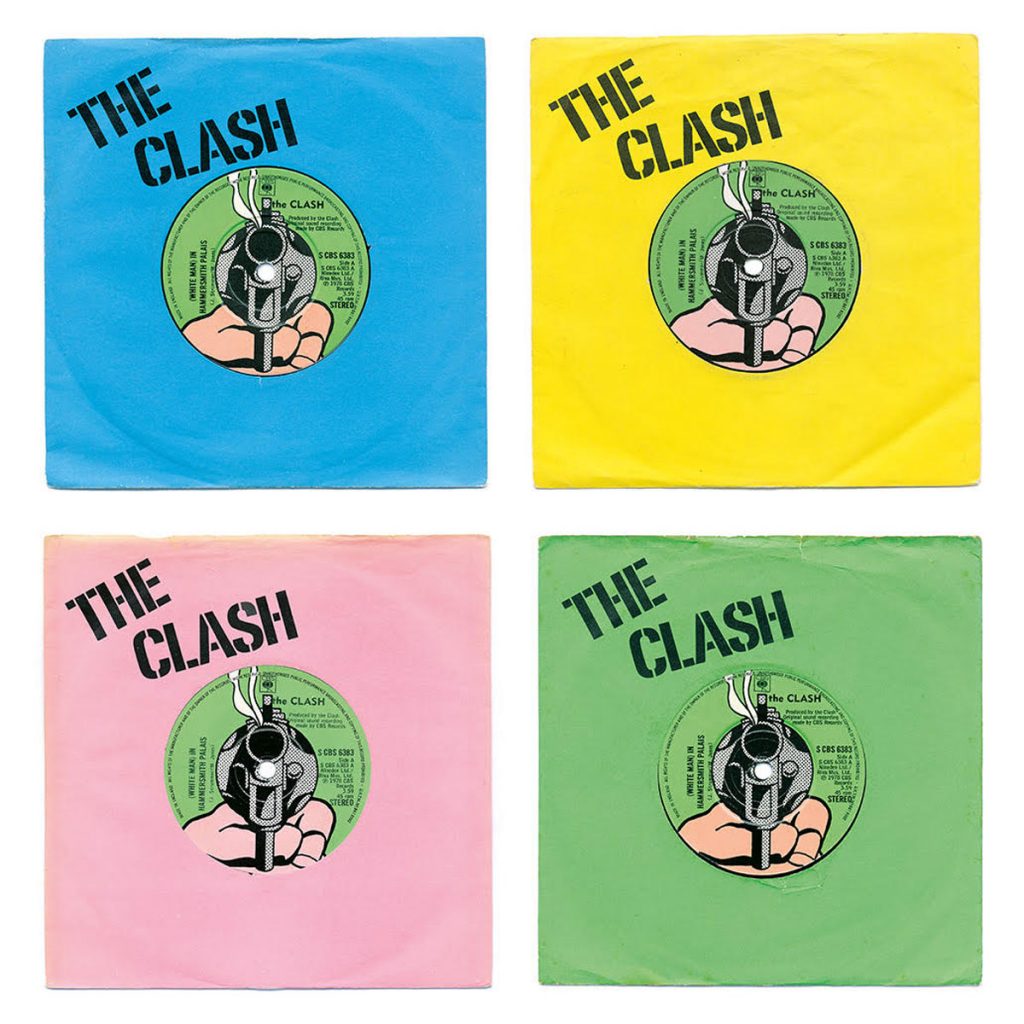

The production, handled by the band and Sandy Pearlman is sparse without being minimal, allowing each element space to breathe whilst maintaining punk’s essential urgency. The decision to keep Strummer’s vocals relatively low in the mix was inspired it forces you to lean in and listen rather than simply absorb. I’ve got four copies and I dread to think how many times my white ears have heard it. It’s impossible to get bored with.

Looking back, “White Man In Hammersmith Palais” stands as perhaps The Clash’s most prescient moment. Its questions about authenticity, appropriation, and the commodification of rebellion feel more relevant now than they did in 1978. ‘If Adolph Hitler flew in today, they’d send a limousine anyway’ they’d also get his opinion of this week’s Nazi atrocity. In an era when punk has been thoroughly sanitised and packaged for consumption, Strummer’s uncomfortable truths about the music industry are prophetic.

The Clash would go on to greater commercial success, but they never again achieved quite this level of self-awareness. “White Man” remains their most honest song, a moment when they looked in the mirror and didn’t like everything they saw, but had the courage to share that reflection with the world.