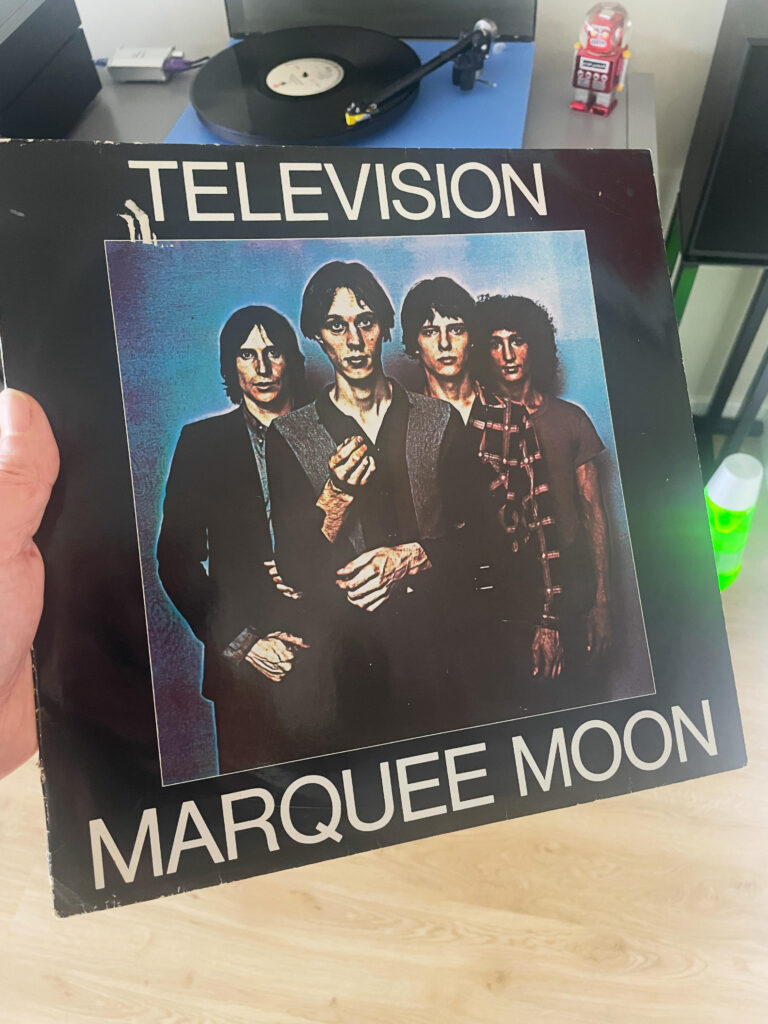

New York in the mid to late Seventies was a city eating itself alive. Bankrupt on paper, feral in practice, littered with burnt-out cars, shuttered storefronts and the low-level menace of economic collapse. Out of this came CBGB, a former biker bar on the Bowery whose original promise of roots music curdled almost immediately into something far more interesting. It became a refuge for the literate, the maladjusted and the terminally dissatisfied. Punk did not so much arrive there as coagulate. And among the first bands to understand that this new language could be stretched, warped and interrogated rather than simply shouted was Television.

Tom Verlaine had already been living inside this world for years by the time Marquee Moon appeared in early 1977. Alongside Richard Hell he had escaped New Jersey boredom, bonded over poetry, speed and a shared belief that rock music should aspire to something sharper than stadium heroics. The Neon Boys, their early incarnation, were less a band than a sketchbook. When Hell departed in 1975 to form the Voidoids taking with him the ripped shirts and confrontational nihilism that would become punk’s uniform, Television were freed from the obligation to perform rebellion in quotation marks. What remained was a band increasingly obsessed with structure, tone and the slow burn of ideas unfolding over time.

CBGB became their proving ground. While other groups detonated through short sets like flash-bangs, Television played long, winding songs night after night, refining them in public. Guitar lines evolved incrementally. Tempos breathed. Solos were not indulgences but arguments. By the time Elektra committed them to tape, these songs had been lived inside, paced around, stripped back and rebuilt. This was not punk as rupture but post-punk as concentration.

The first thing that still startles about Marquee Moon is its clarity. In an era obsessed with distortion and speed, Television chose exposure. Verlaine and Richard Lloyd rejected the familiar hierarchy of rhythm and lead, opting instead for two guitars in constant dialogue. Lines coil, overlap and contradict each other. Melodies appear, dissolve, then reappear altered. Verlaine’s tone is all treble edge and nervous elegance, like fluorescent light flickering on wet pavement. Lloyd grounds the music without weighing it down, muscular but articulate. Beneath them, Fred Smith’s bass moves rather than anchors, while Billy Ficca’s drumming borrows from jazz as much as punk, restless, rolling, impatient with straight lines.

Andy Johns’ production deserves credit for knowing when to disappear. Best known for capturing the brute force of Zeppelin and the Stones, here he allows space to remain space. You hear fingers scrape strings, cymbals decay naturally, air move in the room. Nothing is smothered. Nothing is disguised.

The album unfolds like a series of nocturnal walks through the same city seen from different angles. “See No Evil” announces itself with a rush of romantic urgency, its guitars darting ahead of the beat as if chasing something just out of reach. “Venus” reframes desire as motion and uncertainty, its lyric more impression than declaration. “Friction” hums with paranoia, Verlaine’s voice hovering between detachment and barely concealed anxiety, a perfect document of urban overstimulation.

Then there is the title track, still one of the most audacious statements ever made by a band nominally associated with punk. Ten minutes long, refusing any conventional chorus, it unfolds patiently, methodically. The closing guitar passage is not a solo in the heroic sense but a gradual ascent, Verlaine circling a figure, stretching it, worrying at it, until something breaks open. It feels earned rather than delivered. The listener is trusted to stay with it.

That trust is why Marquee Moon continues to endure. It has never belonged comfortably to its moment. While safety pins and sneers quickly dated, this record remained oddly ageless. Its concerns alienation, romantic idealism, intellectual hunger, the solitude of city life still resonate because they were never tied to fashion. Each generation finds it not as an artefact but as an invitation.

Its influence is everywhere yet curiously diffuse. You hear its DNA in post-punk, indie and art rock, in bands who learned that guitars could converse rather than compete. Sonic Youth, R.E.M., The Strokes and countless others absorbed its lessons, but no one has ever really replicated it. That is because its magic lies in a precise convergence of people, place and temperament that cannot be reverse engineered.

Most new wave guitar records chased velocity and attitude. Marquee Moon chased precision and clarity. It demonstrated that intensity did not require volume, that virtuosity did not need flash, and that punk’s most radical gesture might be patience. Television never surpassed it and never needed to. The album stands complete, self-contained, immune to time.

It remains the sound of New York before it was cleaned up, when danger and beauty shared the same bar stool and ideas mattered as much as noise. A record that asks you to listen closely, think longer, and walk home alone replaying its guitar lines like secret diagrams. Not just one of the greatest new wave guitar albums, but one of the rare rock records that feels inevitable, as though it was always there, waiting for the right minds to tune into it.