Art punk was the moment punk stopped congratulating itself and started asking harder questions. Emerging in the late Seventies as a dismissal of punk orthodoxy and refusal to let that rebellion calcify into costume. It channelled punk’s energy through conceptual art, minimalism, electronics and a deep suspicion of rock mythology. Bands on both sides of the Atlantic treated punk less as a sound than as a method, stripping it down, warping it and, in some cases, dismantling it altogether. What followed was music that alienated as often as it thrilled, and in doing so quietly reshaped everything that came after.

Art punk was never a genre anyone involved bothered to name at the time. Like most labels that later harden into received wisdom, it was applied by critics trying to explain why certain Seventies punk records sounded wilfully strange, emotionally evasive and intellectually awkward compared to the pub-brawl version of punk that nostalgia prefers to freeze-frame. Punk, in the familiar story, was about demolition, a righteous zero hour where rock was burned down and rebuilt from instinct alone. Art punk accepted the need for destruction, then immediately started asking what else might be salvaged from the wreckage. Ideas, for one. Doubt, irony, formal experiment, the suspicion that rock music might actually benefit from thinking too hard about itself.

The distinction was not technical ability or even experimentation for its own sake, but intent. Art punk distrusted punk’s own emerging clichés almost as much as it despised the bloated theatrics of Seventies rock. It had no interest in authenticity as sweat or sincerity, seeing both as just another costume. Instead, it treated rock as a medium to be dismantled, reframed and occasionally mocked. Songs could be cut short, stretched into abstraction or reduced to repetition. Lyrics might read like fragments, slogans or private jokes at the listener’s expense. Performance itself became a problem to be solved, often by draining it of charisma altogether.

New York provided the first sustained proof that punk did not have to mean bluntness. Television looked like a rock band but behaved like a literary salon with amplifiers. Their long, spiralling guitar lines owed more to jazz, poetry and restraint than to punk’s scorched-earth economy. Marquee Moon remains a provocation precisely because it refuses easy allegiance. It is neither punk-as-slogan nor rock-as-spectacle, but something cool, elevated and faintly aloof, a record that suggested punk might be a framework rather than a rulebook.

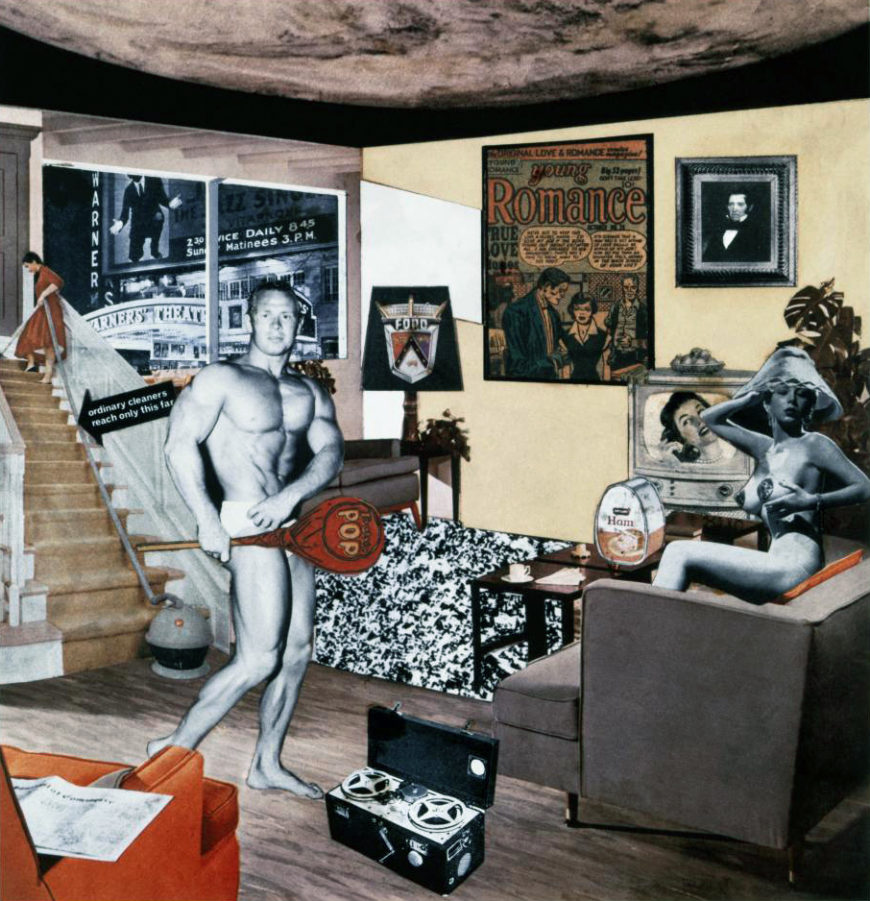

Talking Heads took a different route, draining punk of romance and replacing it with tension. Early Talking Heads records sound like anxiety formalised, clipped rhythms and minimal figures supporting lyrics obsessed with alienation, systems and self-surveillance. Borrowing freely from Dada, conceptual art and pop anthropology, they treated the modern city as both subject and laboratory. Punk here was no longer about escape but about exposure, about making the listener sit with their own discomfort.

If Talking Heads intellectualised punk, Suicide obliterated its remaining assumptions. Drum machines, primitive synthesisers and confrontational repetition stripped rock to its barest, most threatening elements. Suicide were not interested in scenes, solidarity or even approval. Their music functioned like an endurance test, daring audiences to confront boredom, menace and emotional void. In retrospect, they feel less like a punk band than a warning about where punk might end up if it followed its own logic to the extreme.

That logic became even more unstable in the American Midwest. Pere Ubu sounded like industrial collapse rendered as art. Drawing on musique concrète, free jazz and an atmosphere of civic decay, they made punk that felt genuinely alien. The Modern Dance was not a refinement of punk but a mutation, proving that the form could absorb noise, abstraction and paranoia without becoming polite. It is no accident that later British post-punk musicians treated Pere Ubu less as peers than as evidence that almost anything was possible.

Conceptual control reached its most explicit form with Devo, who turned the band into a piece of performance art. Their theory of de-evolution, identical uniforms and mechanical rhythms drained rock of humanist pretence. Devo’s satire was not playful but forensic, exposing the stupidity and conformity beneath American optimism. Punk, for them, was simply the most efficient delivery system for bad news.

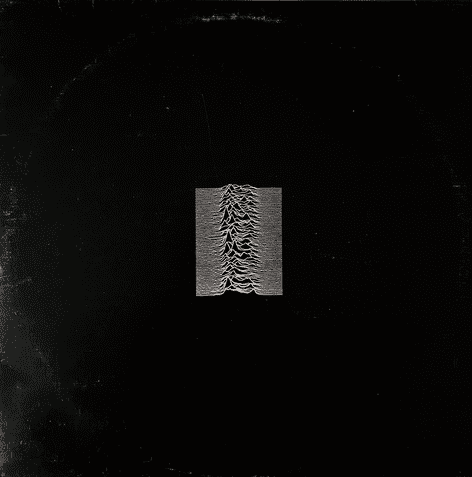

In Britain, art punk arrived not as an opening statement but as punk’s second thought. Once the safety pins were commodified and the outrage routinised, bands began interrogating what punk could still do. Wire understood earlier than most that punk’s real weapon was not speed or volume but reduction. Pink Flag treated songs as raw material, slogans rather than statements. What followed was even more radical: a steady erasure of punk itself in favour of electronics, abstraction and distance. Wire did not betray punk. They completed it, then moved on.

Magazine offered a more overtly literary escape route. Howard Devoto replaced punk’s blunt nihilism with modernist unease, his lyrics circling alienation, desire and power rather than simply rejecting everything in sight. The music incorporated keyboards and art-rock structures without lapsing into comfort. Magazine mattered because they insisted that punk intelligence did not have to disguise itself as rage.

If some of this still looked like rock music, Throbbing Gristle arrived to ensure that nobody in the U.K. at least felt safe confusing art punk with entertainment. Emerging directly from the performance art collective COUM Transmissions, Throbbing Gristle treated sound as material and provocation as principle. Tape loops, electronics, transgression and deliberate moral discomfort replaced songs altogether. Their work sits at the outer edge of art punk, but it is essential, because it demonstrates the endgame of punk taken seriously as an artistic idea rather than a style. Once you accept that anything can be questioned, you eventually question whether music needs to behave like music at all.

The influences that shaped these bands rarely pointed backwards. Minimalism suggested repetition without payoff. Krautrock offered propulsion without blues heritage. In praise of negative space Dub revealed space and absence as compositional tools. Conceptual art legitimised irony, framing and emotional detachment. Above all, art punk rejected sincerity as a moral virtue. Authenticity, as rock had defined it, was exposed as another sentimental fiction.

What makes art punk still matter is how badly it fits with the way punk is now remembered. Contemporary punk nostalgia prefers leather jackets, simple narratives and the comforting lie that rebellion can be endlessly replayed without consequence. Art punk tells a harsher truth. It says that punk only mattered when it refused to behave, when it alienated its audience, when it dismantled its own myths faster than the market could package them. Very little of that spirit survives in a culture that treats punk as heritage branding.

Art punk was not about saving punk. It was about proving that punk was disposable. That once its job was done, the only honest response was to push it somewhere uncomfortable and leave it there. The real scandal is not that punk ended, but that so much of what followed pretended it never asked these questions at all.