Ian Curtis is routinely described as a singular figure in post-punk, yet the language used to discuss his work rarely escapes mythology. His lyrics are invoked as evidence of torment, prophecy or doomed authenticity, framed almost exclusively through biography rather than method. What is missing from much of the commentary is a sustained examination of how the writing actually works, its sources, its discipline, its formal intelligence. Curtis was not merely a vessel for darkness but a writer engaged with literary traditions that extend well beyond rock music, and his song lyrics reward the kind of close reading usually reserved for poets on the page. This essay approaches his work not as legend or lament, but as literature: constructed, deliberate, and deserving of serious critical attention.

Ian Curtis and the Literary Intelligence of Joy Division

Ian Curtis never called himself a poet, and nothing in his work suggests an interest in that designation. Yet his lyrics for Joy Division display a literary intelligence rare not only in post-punk but in popular music more broadly. Where many contemporaries relied on provocation, manifesto or abstraction-as-attitude, Curtis wrote with a precision that suggests sustained engagement with language as a moral and psychological instrument. His words do not posture; they observe, diagnose and endure. Stripped of melody and arrangement, they continue to function as texts. That endurance is the mark of literature, not accident.

Curtis’s writing does not emerge from rock tradition so much as runs adjacent to it. Its lineage lies elsewhere: modernism’s fractured consciousness, expressionism’s emotional extremity, confessional poetry’s refusal of discretion, symbolism’s reliance on implication rather than declaration. These influences are not decorative. They structure the work at the level of syntax, imagery and omission.

The modernist inheritance is clearest in Curtis’s handling of fragmentation. Like T.S. Eliot, he constructs meaning through discontinuity rather than narrative development. Decades, Joy Division’s closing statement, is exemplary. The opening question, “Where have they been?” is not addressed to a listener but suspended in space, unanswered. What follows is a series of temporal dislocations: “We waited too long / Through the slackened seas / And the years have gone.” The verbs slide between past and present, action and stasis. Nothing happens, yet everything has already happened. The effect is not despair but exhaustion, a consciousness worn thin by duration itself.

This is not mere mood. Curtis understands time as pressure. His characters are not alienated in the abstract; they are eroded. Like Eliot’s city dwellers, they are trapped within systems that outlast and outscale them. Manchester’s post-industrial landscape is not a backdrop but a condition, present in the songs as corridors, factories, streets without destination. The environment does not oppress through spectacle but through repetition.

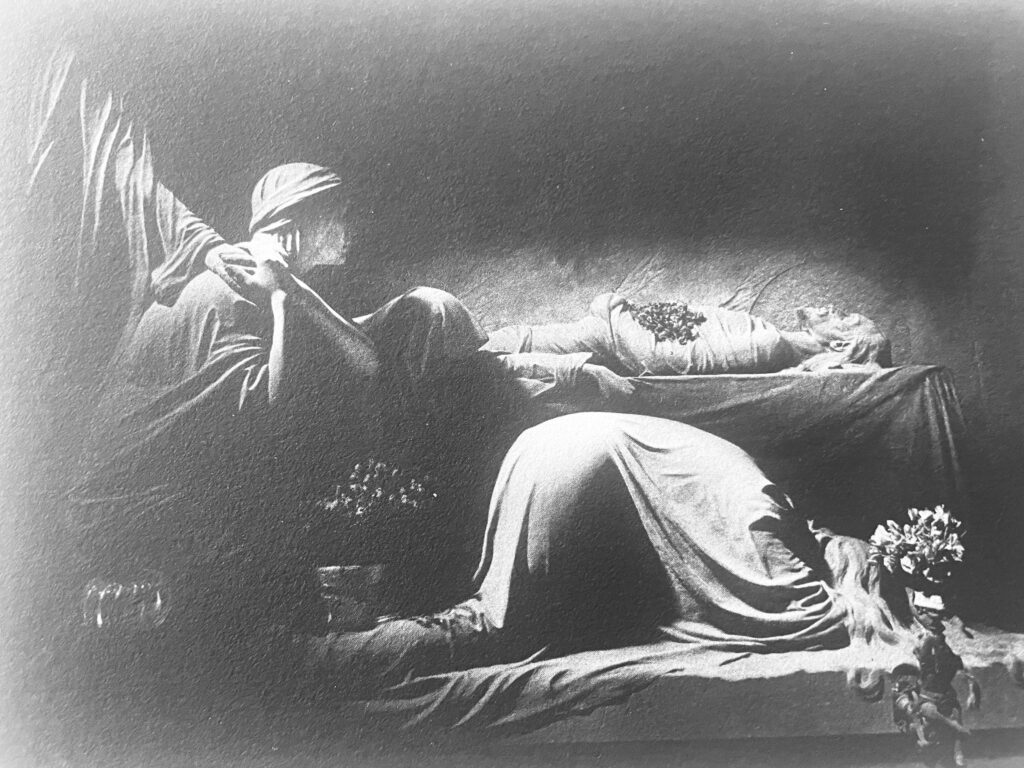

German expressionism offers a second key. Curtis was drawn to Weimar-era art for its insistence that psychological truth mattered more than realism. Expressionist distortion exaggerates form to make interior states visible. Curtis achieves something similar through restraint rather than excess. She’s Lost Control is written with clinical detachment, the language stripped of emotive cues. The seizure is described, not interpreted. That refusal of commentary amplifies the horror. We are not told what to feel; we are placed inside a system that cannot accommodate vulnerability.

Expressionist poetry deals in absolutes; guilt, decay, transcendence, annihilation. Curtis’s lyrics operate in the same register. There is little moderation. Emotional states are terminal. In Heart and Soul, the repetition of the title phrase functions less as affirmation than erosion, each return diminishing its meaning until language itself appears to fail. This is not confession but exposure, an anatomy rather than a diary.

The confessional poets provide another point of contact, though Curtis is more disciplined than the term suggests. Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Robert Lowell broke with lyric decorum by writing directly about mental illness and death, yet their power lay in clarity rather than self-dramatisation. Curtis shares that discipline. New Dawn Fades is often read retrospectively as prophecy, but its strength lies in how carefully it avoids spectacle. “A loaded gun won’t set you free” is not a cry for help but a statement of limits. Violence, even self-directed, offers no transcendence. The lyric denies release even as it gestures toward it.

Similarly, Isolation gains its force from direct address stripped of metaphor. “Mother, I tried, please believe me.” The line is devastating precisely because it refuses poetic camouflage. There is no symbol to interpret, no image to decode. It reads like testimony, not performance. As with Plath, the private becomes legible because it is not aestheticised beyond necessity.

Curtis’s debt to symbolism complicates this clarity. The French symbolists believed poetry should suggest rather than explain, building meaning through resonance rather than statement. Atmosphere is perhaps the purest example of Curtis working in this mode. The song is built almost entirely on repetition and instruction: “Walk in silence / Don’t walk away, in silence.” The meaning never settles. Is silence protective or fatal? Is walking away an act of survival or abandonment? Curtis refuses to decide. The lyric functions as an environment rather than an argument, its ambiguity sustained rather than resolved.

This method distinguishes Curtis from many of his peers. He was not interested in narrative confession or social reportage. His lyrics build psychological architecture that mirrors Martin Hannett’s production: reverberant, enclosed, distant. Language and sound operate as parallel systems. Words do not explain the music; they inhabit it.

Importantly, this seriousness was not accidental. Curtis read constantly; Kafka, Ballard, Burroughs, Dostoevsky, and wrote with discipline. He revised. He understood rhythm and weight. He avoided cliché not out of aesthetic snobbery but because cliché collapses meaning into familiarity. Silence mattered as much as statement. What is omitted carries as much force as what is declared.

There are limits to Curtis’s range. His emotional palette is narrow, his imagery recurrent. One could argue that his work risks monotony when detached from Joy Division’s musical context. But limitation is not the same as weakness. Within his chosen territory; alienation, control, collapse, Curtis achieved a density and coherence rare in popular songwriting.

Rock criticism has often struggled to engage with writing that demands close reading. Curtis’s lyrics are frequently treated as artefacts of biography rather than texts in their own right, framed by his death rather than his method. That approach diminishes the work. These songs reward analysis because they are constructed, not merely felt.

If Curtis had written for the page rather than the stage, his work would invite comparison with late-twentieth-century poets concerned with urban modernity and psychological fracture. That he chose the microphone does not invalidate the seriousness of the writing; it merely situates it differently. His lyrics occupy an unstable space between literature and performance, resistant to easy categorisation.

Ian Curtis did not invent post-punk’s darkness. He articulated it. Drawing on modernism’s fragmentation, expressionism’s extremity, confessionalism’s clarity and symbolism’s atmosphere, he synthesised a language capable of bearing emotional weight without collapse. His work remains rigorous, economical and unsentimental.

The songs endure not because of tragedy but because of craft. They read as poems because they were written with a poet’s attention to language, its pressure, its limits, its failures. Curtis understood that words could not save you, but they could tell the truth about why they wouldn’t. That, finally, is his literary achievement.

Ian Curtis 1956-1980.