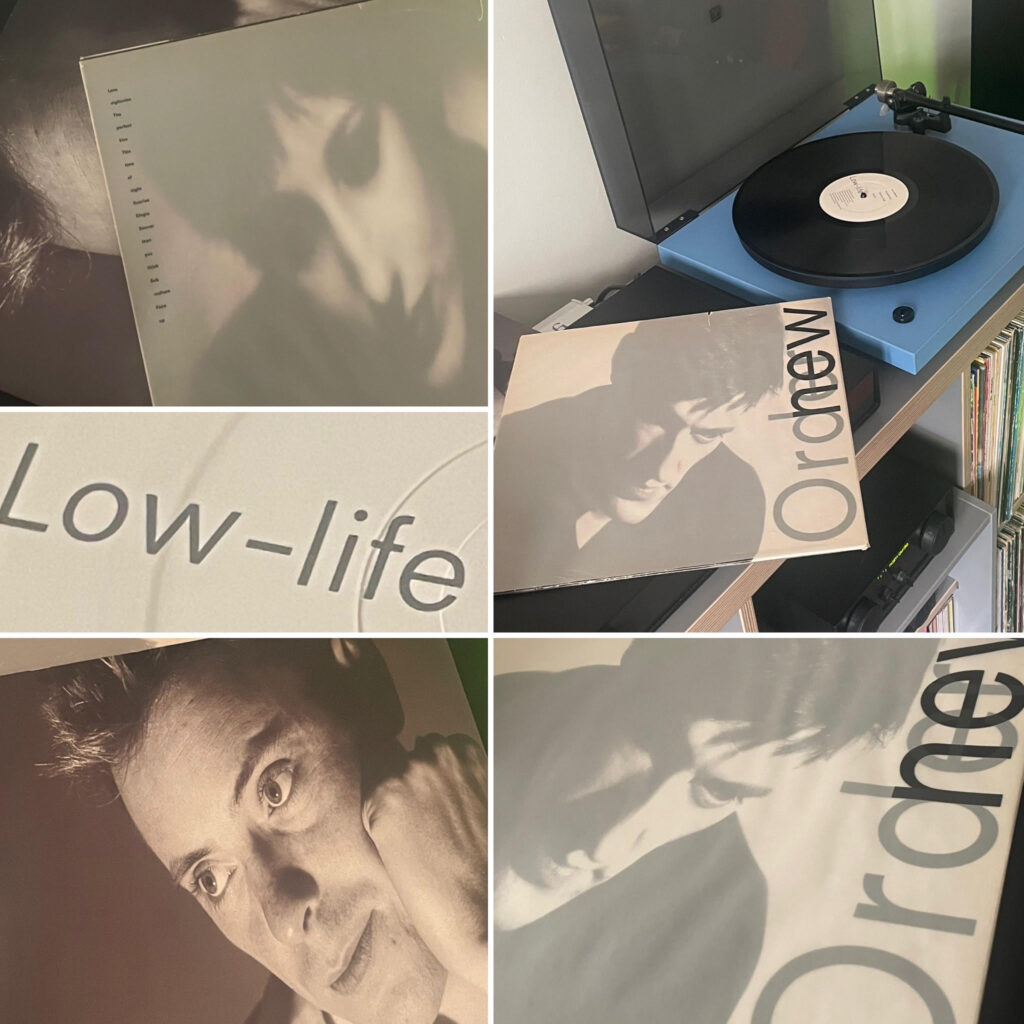

New Order – Power, Corruption & Lies: A Retrospective Review

The Sleeve That Rewrote the Rules

Before a note of Power, Corruption & Lies reaches the ears, the eye is confronted with Peter Saville’s sleeve, a design that has gathered its own mythology over the passing decades. At first glance it is simply a reproduction of Henri Fantin-Latour’s 1890 still life of roses, delicate and faintly melancholic, a far cry from the cold geometry Factory Records had become known for. Yet the real twist lies in the seemingly innocuous coloured blocks that sit in the corner like a quiet rebuke to conventional typography. Long regarded by fans as a form of visual poetry, the blocks were eventually revealed to be Saville’s attempt at a coded alphabet, a kind of secret linguistic handshake that gave the record an air of clandestine modernity.

What has emerged through later interviews is just how mischievous the whole thing was. Saville had been increasingly bored with the constraints of standard lettering, so he set about devising a system that would let him “write” the band’s name and album title without actually writing anything at all. Factory, in characteristically perverse fashion, embraced the idea. The result was a jacket that felt like a puzzle box, a Victorian painting interrupted by a futuristic key, a design that made no immediate sense yet seemed perfectly in step with New Order’s own uncertain transition from the gloom of their past into something more colourful and unpredictable.

Over time the sleeve has come to be seen as a statement of intent. It suggested that this was not merely another post-punk artefact, but a curious hybrid of heritage and innovation. It also set the tone for countless later designers who treated album packaging as a riddle rather than a label. Even now it retains that rare magic, the sense of being both timeless and ahead of its time, a piece of art that hinted, long before the music began, that New Order were about to reinvent themselves.

The Music That Reprogrammed The Band

History tends to sand down the sharp edges of even the most tumultuous bands, but in the case of New Order’s Power, Corruption & Lies, the decades have only sharpened its silhouette. It remains an album perched squarely on the fault line between grief and reinvention, the moment Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook, Stephen Morris and Gillian Gilbert turned their backs on the monochrome shadows of Joy Division and stepped, blinking, into a brash new technicolour world, although one still streaked with dread.

Now with more than forty years of hindsight and a small library’s worth of scholarship behind it, the album feels less like a second album (I detest sophomore) release and more like a manifesto. The lingering presence of Ian Curtis haunted Movement, but here the ghosts do not dictate terms; they merely observe. The record opens not with a funereal echo from the Factory corridors, but with “Age of Consent”, a bright, jangling rush of liberation that still carries a nervous quiver beneath its surface. Sumner’s vocal, tentative and slightly frayed, sounds like someone learning to speak again. Hook’s bass, by contrast, strides forward with the immodest confidence of a man who knows he is holding the melodic centre of gravity.

What modern listeners can appreciate, thanks to years of interviews and excavated studio notes, is just how bare-bones their toolkit really was. The band were teaching themselves synthesisers on the fly; Gillian Gilbert in particular has since recalled how she pieced together melodies with a mixture of curiosity and blind faith. Stephen Morris was programming early drum machines in ways their manufacturers had never intended. One later admitted he genuinely had no idea how Morris coaxed certain patterns out of the Oberheim DMX without the casing overheating. The album’s mechanical pulse, so crisp and self-assured to contemporary ears, was in fact held together by the sheer nerve of four people who barely knew if the circuitry would hold until the final mix.

“Blue Monday” inevitably casts a long shadow whenever the PCL era is mentioned, though it technically sits outside the album. But it was the PCL sessions, along with the band’s growing fascination with the dancefloor, that birthed it. Factory archivists unearthed, years later, a handwritten note from designer Peter Saville estimating how many copies the label would need to sell just to break even, owing to the sleeve’s notoriously expensive die-cut floppy-disc design. They underestimated wildly. The single became a commercial leviathan, and its success dragged Power, Corruption & Lies along behind it like a passenger stumbling onto the last train home.

The album’s mid-section still feels like a crystallisation of New Order’s internal tug-of-war. There is the icy romanticism of “Your Silent Face” (with Sumner’s now-infamous “Why don’t you piss off?”), the post-punk scaffolding that creaks through “Ultraviolence”, and the synth-pop shimmer of “Leave Me Alone”, a track that sounds like two elevated hands reaching simultaneously for joy and resignation. Critics have long debated whether PCL is the moment New Order shed their Joy Division skin or merely learned to live with the seams showing, but in truth it is both, a record that understands transformation not as an erasure but as an accumulation.

One of the more intriguing details unearthed in the years since comes from engineer Michael Johnson, who revealed in a 2010 retrospective that the band often worked in near-total silence between takes, communicating in nods and half-gestures. “It was like watching people rebuild a house they did not remember demolishing,” he said. That sense of fragile reconstruction thrums from the record’s core. Despite its reputation as the dawn of New Order’s dance era, PCL is an album built on restraint, with spaces left open, lines left hanging, and machines nudged into emotional service.

Today, Power, Corruption & Lies stands as the first true statement of what New Order were capable of when freed from both tragedy’s grip and expectation’s weight. It is a record that neither rages nor mourns, but simply moves forward, quietly radical, defiantly awkward and utterly singular. The decades have clarified its position in the canon, not as a footnote to Joy Division and not merely as a stepping stone to the superclub-friendly New Order of the 1990s, but as a work of invention from a band still learning how to be itself.

And like the best of New Order’s output, it remains a reminder that sometimes the future begins not with a bang but with a hesitant synth line, a guiding bass melody, and four people trying to find their footing on the other side of loss.