From the trenches of Spain to TikTok activism: How each generation finds its own way to fight injustice. I take a look at what defines moral courage across nearly a century of activism.

The photographs are fading now, fresh faces, serious beneath berets, holding rifles they barely knew how to use – ‘but if they could shoot rabbits they could shoot fascists’. They were clerks and miners, teachers and labourers, probably born around the time of World War One and united by nothing more than a conviction that fascism had to be stopped. In the winter of 1936, they kissed their wives and girlfriends goodbye at Victoria Station and caught the boat train to Paris, then walked across the Pyrenees to join a war that wasn’t theirs.

Ninety years later, their grandchildren are hunched over smartphones and laptops, typing furiously. Organising boycotts of Israeli goods, coordinating with activists in Manchester and Glasgow through encrypted messaging apps. Their enemy is different, their methods transformed, but the impulse, that peculiar British inability to mind one’s own business when faced with injustice, remains precisely the same.

This is the paradox of moral courage: it appears constant across generations, yet manifests in forms so different that each age struggles to recognise virtue in its predecessors or descendants. The young man boarding the train to Spain in 1937 and the student sharing TikTok videos about Gaza today are separated by everything except the essential thing: the refusal to be a bystander.

The Weight of History

The Spain volunteers were products of their time in ways they barely understood. They had grown up on tales of The Great War, that ghastly demonstration of what happened when good men did nothing whilst imperialism organised itself a war machine prepared to send tens of thousands to their deaths for twenty yards of Flanders. The unemployment queues of the twenties and thirties had given them first-hand experience of how political decisions destroyed ordinary lives. When Hitler began his march across Europe, they possessed a clarity of vision that seems almost enviable today.

It was a simple decision, Fascism was visibly, unmistakably evil. The choice was binary: fight or surrender civilisation itself.

Their media diet reinforced this clarity. The Left Book Club, founded by Victor Gollancz in 1936, distributed serious political analysis to tens of thousands of subscribers. These weren’t soundbites or slogans, but hefty volumes that provided comprehensive frameworks for understanding the world. Members read Orwell’s “The Road to Wigan Pier” and Edgar Snow’s “Red Star Over China” with the same intensity that previous generations had reserved for scripture.

The Communist Party of Great Britain, despite its relatively small membership, provided intellectual structure for much of the anti-fascist movement. Party members attended evening classes in Marxist theory, studied the writings of Lenin and Stalin, and engaged in lengthy debates about the contradictions and solutions dialectical materialism. It was serious, systematic, and utterly certain of its moral foundation.

This certainty came at a cost. The volunteers who returned from Spain, barely half of those who went, found themselves isolated in a society that preferred to forget their sacrifice. The government had banned participation; employers dismissed them as troublemakers; families often disowned them. They had acted on their convictions and paid the price.

The Television Generation

By the 1960s, everything had changed. Television brought warfare into British sitting rooms with an immediacy that print could never achieve. The Vietnam War, though fought 8,000 miles away, became as real as the evening news. Young people watched napalm falling on villages and made their moral calculations accordingly.

But television also fragmented attention. The Spain volunteers had spent years preparing for their moment of choice, reading widely and thinking deeply. The sixties activist might encounter a crisis on Tuesday evening news and be marching against it by Saturday afternoon. The intensity was different, more diffuse but potentially more democratic.

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament demonstrated this new model perfectly. Founded in 1958, it brought together people across traditional political divides, vicars and communists, housewives and students, united by a single issue rather than a comprehensive ideology. The annual march from Aldershot to London became a ritual of moral witness, drawing tens of thousands who might never have joined a political party.

“We weren’t trying to overthrow capitalism,” recalls Canon John Collins, an English-American priest, activist, and one of CND’s founders. “We were simply trying to prevent the incineration of humanity. It was a more modest ambition, but in its way equally urgent.”

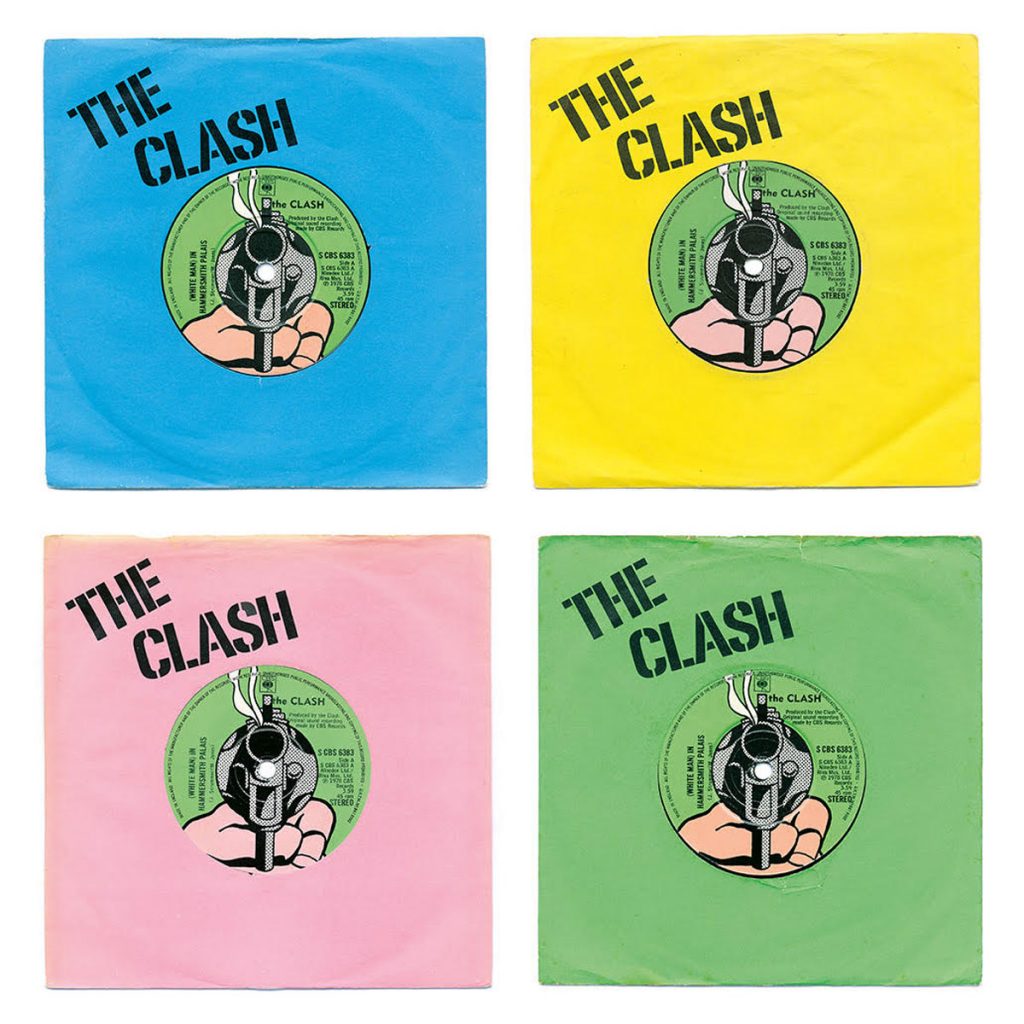

The anti-apartheid movement perfected this approach over the following decades. Beginning in the early sixties, it combined traditional tactics, boycotts, protests, lobbying, with innovative approaches that made distant injustice personal and immediate. The boycott of South African goods meant that every shopping trip became a political choice. The campaign against sporting contacts meant that cricket and rugby matches became sites of moral conflict.

This movement also pioneered the use of celebrity endorsement. The 1988 Wembley Stadium tribute concert for Nelson Mandela reached a global audience of 600 million people, using entertainment to advance political goals. It was a technique that would become standard practice for later campaigns, but still revolutionary at the time.

The Digital Natives

Walk through any university campus today and you’ll find young people who carry the world’s suffering in their pockets. Their iPhones buzz with updates from Gaza, Myanmar, and Ukraine. They receive real-time footage of air strikes and refugee camps, police violence and peaceful protests. The question is not whether they know about global injustice, they’re drowning in it, but how they can possibly respond to such overwhelming information.

Previous generations had the luxury of ignorance, today’s students know more about global crises than foreign correspondents did thirty years ago. But knowledge without power can be paralysing.

The response has been to develop new forms of engagement that previous generations struggle to recognise as political action. Hashtag campaigns can generate millions of posts within hours. Online fundraising ‘crowdfunding’ can raise substantial sums for distant causes. Viral videos can shift public opinion more rapidly than years of traditional campaigning.

The #MeToo movement demonstrated the power of these new tools. Beginning with a simple hashtag, it created a global conversation about sexual harassment that achieved swift legislative changes and cultural shifts across dozens of countries. The climate activism organised through social media has brought millions of young people onto the streets in coordinated global protests.

Yet digital activism faces unique challenges. The rapid news cycle means that even severe crises can replaced in the news and disappear from public attention within days. This can be manipulated by senior management of media organisations in favour of their own political affiliations. The personalisation of social media means that activists often speak primarily to those who already agree with them – an echo chamber. The volume of information can lead to compassion fatigue, where audiences become numb to repeated exposure to suffering – it becomes less painful to scroll on by.

The Palestine Question

Nothing illustrates these challenges more clearly than contemporary activism around Palestine and specifically Gaza. Social media platforms enable rapid sharing of information and imagery from the territory, creating immediate and highly emotional connections between British audiences and distant suffering. Young people encounter footage of destroyed homes and dead or severely injured women and children with an immediacy that traditional media could never achieve. Traditional media older generations might recognise is perpetually behind the curve now.

The movement has achieved remarkable success in shifting public opinion, particularly among younger demographics. Polls consistently show that 18-34 year olds are more likely to support Palestinian rights than their parents’ or grandparent’s generation. This shift has occurred largely through peer-to-peer education disseminated via social media platforms.

Digital tools have also enabled new forms of economic pressure. Some activist movements use apps to help consumers identify targeted products, whilst campaigns against particular companies can generate thousands of emails and social media posts within hours. University students have occupied buildings and demanded divestment from Israeli companies, echoing the tactics used against apartheid South Africa – specifically contra to government policy causing an authoritarian shift in the rules around assembly and organising protest.

But the digital nature of much contemporary activism also creates vulnerabilities. Online harassment can be severe and persistent. Employers increasingly monitor social media activity. The Israeli (also Russian and Chinese) government has developed sophisticated techniques for countering digital campaigns, including the use of artificial intelligence to generate pro-Israeli content. Just this week the Israeli-supporting US Government has severely sanctioned Francesca Albanese, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, a pro bono lawyer employed officially by the United Nations to report on the abuse of human rights and contraventions of international law. The contradiction is stark, they host an internationally wanted world leader while sanctioning a person working for free trying to protect innocent civilians. This is not unique to modern democracies, the UK proscribes civil disobedience organisations, both human rights and climate, arresting peacefully protesting grandmothers while simultaneously hosting murderous former ISIS leaders. Geopolitics, hard and soft power work in mysterious ways.

The surveillance tools are more powerful as are the forces arrayed against change. Young activists today face surveillance and repression that previous generations couldn’t imagine.

The Persistence of Conscience

Despite these challenges, certain constants persist across generations. Each era produces individuals willing to sacrifice personal comfort for abstract principles. The 1930s volunteer who risked death in Spain, the 1980s activist who spent weekends outside the South African embassy, and the contemporary campaigner who faces online harassment for posting about Gaza all demonstrate the same fundamental impulse: the refusal to remain passive in the face of injustice.

The forms of engagement have multiplied rather than simply evolved. Today’s most effective activists often combine traditional tactics with digital tools. They might use social media to organise, but still attend physical protests. They might share information online, but also donate money and contact elected representatives.

Take Greta Thunberg, who began her climate activism with the most traditional gesture imaginable, a solitary protest outside the Swedish parliament. Yet her message spread globally through social media, inspiring millions of young people to stage their own protests. The combination of personal witness and digital amplification created a movement that achieved more in two years than traditional environmental groups had managed in decades. The cost to her personally, years of targeted abuse and harassment as she expands her activism from climate to human rights – recently her own courage and fame protecting those around her.

The Measure of Moral Courage

The temptation is always to romanticise past forms of engagement whilst dismissing contemporary ones. The Spain volunteers have achieved heroic status in progressive mythology, whilst today’s digital activists are often dismissed as “slacktivists” who mistake online participation for real engagement.

This misses the essential point. The British volunteers to Spain were no more inherently virtuous than today’s activists; they simply operated within different constraints and opportunities. They faced a clear enemy at a time when physical courage was the obvious response. Today’s activists face more widespread threats in a world where information warfare is often more important than physical confrontation.

The measure of any generation’s moral response to international crises should not be whether they replicate the actions of their predecessors, but whether they fully utilise the tools and opportunities available to them. By this standard, contemporary British activism, from the climate movement to international solidarity campaigns, demonstrates both the persistence of moral concern and the creativity required to address global challenges in an interconnected world.

The man who walked across the Pyrenees to fight fascism and the student who organises boycotts through Instagram are part of the same tradition. They have recognised that injustice anywhere threatens justice everywhere, and they have refused to be bystanders. The methods change, but the conscience remains constant.

Perhaps that is enough. Perhaps that is everything.

PS. If you are reading in the U.K. I suggest switching to Channel 4 News.