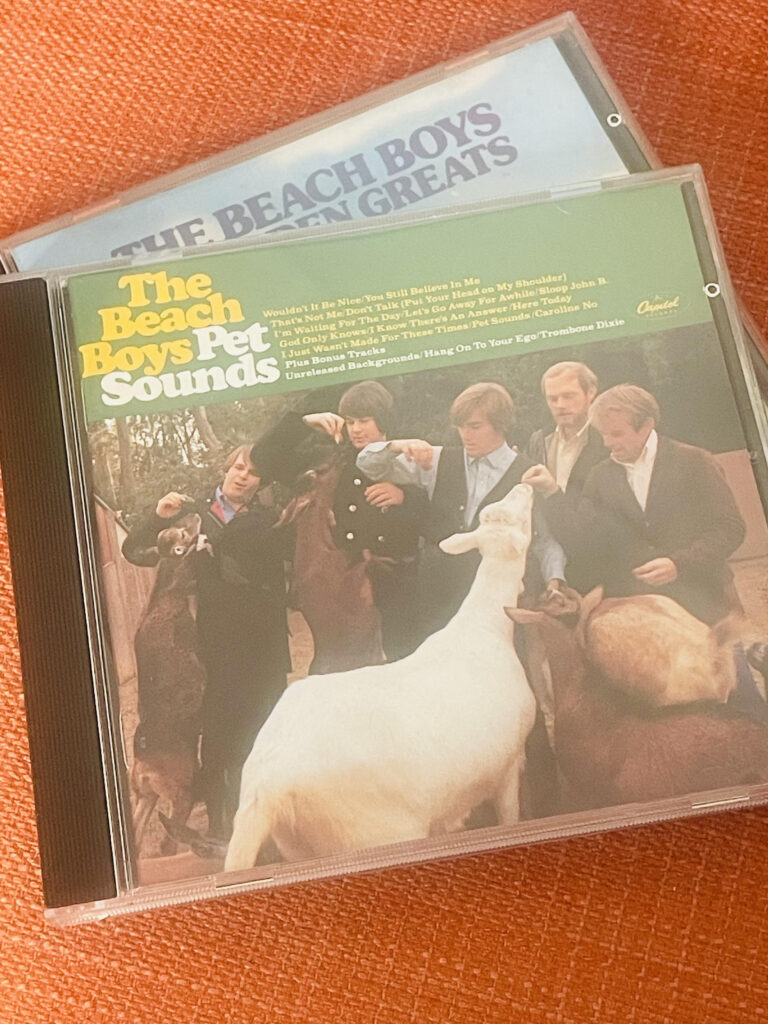

From surf music to sonic revolution: why Pet Sounds remains pop’s most extraordinary achievement and Brian Wilson’s last coherent masterpiece.

At the passing of the musically creative genius Brian Wilson, I’ve written this sixth decade reappraisal of The Beach Boys album Pet Sounds as a meditation on one of music’s most extraordinary creative achievements. A work that represents both the culmination of years of obsessive craft development and the sound of consciousness chemically expanded beyond conventional limits.

From a technical, production and arrangement perspective Pet Sounds – compared to literally everything produced beforehand anywhere is like comparing a Chevy Bel Air with a Saturn 5 rocket plus Apollo orbiter and lander. But this quantum leap didn’t emerge from nowhere. Wilson had been methodically building towards this moment since 1962, spending obsessive hours in Gold Star Studios, studying Phil Spector’s wall of sound techniques firsthand. By the time of “I Get Around,” he’d already developed an uncanny ability to hear individual instruments within dense arrangements and was experimenting with unconventional microphone placement that suggested an intuitive understanding of acoustic space.

Between 1963-1965, Wilson systematically expanded his musical vocabulary in ways that would prove crucial to Pet Sounds’ revolutionary impact. His harmonic progression from basic surf progressions to the complex jazz-influenced arrangements of “California Girls” and “Help Me Rhonda” shows us his systematic musical development. Wilson was absorbing Bach, studying Four Freshmen arrangements, and incorporating diminished chords and unexpected modulations. Simultaneously, he was cataloguing an increasingly exotic instrumental palette – harpsichord on “When I Grow Up,” orchestral arrangements on “The Warmth of the Sun,” and unusual percussion combinations that would later bloom into Pet Sounds’ bicycle bells, dog whistles, and Coca-Cola bottles.

Perhaps most significantly, Wilson’s vocal arrangements grew increasingly complex through albums like “Today!” and “Summer Days.” He was developing techniques for recording his own voice multiple times to create impossible harmonies, essentially turning himself into a one-man choir. This technical mastery meant that when his consciousness expanded, he had the tools to translate internal complexity into actual sound.

The emotional development running parallel to this technical growth was equally crucial. Wilson’s evolution from teenage surf fantasies to the adult anxieties about love, isolation, and belonging that permeate Pet Sounds wasn’t simply chemical revelation – it was the natural progression of a sensitive artist confronting the complexities of the human condition.

Substitute liquid hydrogen mixed with oxygen and a lit match with LSD and a musical genius and you’ll get Wouldn’t It Be Nice and God Only Knows here, and later Good Vibrations – his unique sounding music incredibly recorded on limiting four track equipment. It famously shook Paul McCartney to up his game and Bob Dylan has since remarked “Brian recorded Pet Sounds with four tracks, nobody else could record it with one hundred”.

Listen to Pet Sounds now, knowing what we know about Wilson’s lysergic acid adventures, and those otherworldly arrangements make perfect sense. Of course “God Only Knows” sounds like it was transmitted from heaven to Wilson’s rewired consciousness while operating on a papal frequency the rest of us can’t even tune into. But the genius wasn’t that Wilson was taking drugs – the entire suburb of Laurel Canyon was tripping in ‘66. The genius was that he was disciplined enough, focused enough, and talented enough to document his pharmaceutical journey with obsessive precision, using a toolkit of techniques he’d spent four years perfecting.

“I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times” we thought it was teenage alienation set to music. That maybe a prophetic autobiography from someone who’d already glimpsed his own future. The Theremin isn’t just an exotic instrument; it’s the faraway sound of Wilson’s cognition misfiring – in real time, beautiful but disturbing. But Wilson had been experimenting with unconventional instrumentation for years – this wasn’t random psychedelic inspiration but the culmination of systematic sound exploration.

The production techniques he described as derivative of Phil Spector and revolutionary in ‘66 now reveal themselves as the work of someone literally on another level. Wilson wasn’t just multi-tracking vocals he was seemingly attempting to capture the sound of multiple personalities having a conversation inside his head. Yet this vocal architecture built upon years of development – turning himself into a one-man choir through techniques he’d been perfecting since the early Beach Boys recordings.

Those impossibly complex arrangements on tracks like “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” aren’t showing off; they’re the musical equivalent of someone trying to make real something only he could hear in his imagination in ways difficult or impossible for lesser mortals to comprehend. But they’re also the work of someone who’d spent years absorbing Bach, studying the ‘Four Freshmen’ arrangements, and incorporating jazz harmonies that as mentioned most pop musicians couldn’t even hear, let alone execute.

What’s terrifying and brilliant is how Wilson managed to harness his disintegrating mental state and turn it into art. The drugs that were slowly destroying his grip on reality were simultaneously opening doorways to musical territories that simply don’t exist for the chemically unenhanced, a musical Doors Of Perception and where, see Aldous Huxley, heaven eventually becomes hell. Every overdub, every bizarre instrumental choice, every impossible vocal arrangement was Wilson obsessively following his rewired neural pathways to their logical conclusion – but using a musical vocabulary he’d been building methodically for years.

“Pet Sounds” the instrumental also makes more sense when viewed through this lens – it’s the sound of Wilson’s mind trying to process information through a consciousness that’s been chemically recalibrated. Those conversations between saxophone and percussion aren’t random; they’re Wilson translating internal dialogues that were becoming increasingly complex as his brain chemistry shifted, but executed with the instrumental sophistication he’d been developing since his earliest studio experiments.

Most people who’ve ingested that much LSD, in greater quantities than Syd Barrett, a similarly progressive British musical casualty and founding member of Pink Floyd, can barely tie their shoelaces, let alone orchestrate 40-piece arrangements that still sound futuristic. Wilson could do this because he’d already built the technical foundation – the chemicals didn’t create his abilities, they liberated them from conventional constraints.

But here’s the truly heartbreaking bit – we can now hear Pet Sounds as Wilson’s last completely coherent statement before the drugs and the pressure and the sheer weight of his own vision crushed him. Every perfect detail, every impossibly beautiful moment, every note that shouldn’t work but does – it’s all evidence of a mind operating at peak capacity whilst simultaneously consuming itself.

The comparative commercial failure in the America of 1966 was simply because the market wasn’t ready for avant-garde popular music made by someone now playing piano 24/7 seated in a sandbox. They wanted surf music from those nice clean-cut boys; what they got was the sound of now unkempt, long haired and bearded genius having a nervous breakdown in slow motion set to beautiful melodies. Remember that alongside the pressure generated creatively there’s financial pressure from Capitol who are ploughing dollars into the project. Yet another stress that’s under appreciated and rarely mentioned. Yes the total cost of a project might be oft quoted but not the absorption often by one sensitive creative person.

Wilson’s story since Pet Sounds – the breakdown, the bedroom years, the pills, the decline – only makes this album more precious. It’s the sound of someone touching something spiritual whilst burning up in the atmosphere of their own obsession. He gave us a glimpse of what’s possible when infinite talent meets unlimited chemical enhancement, and then paid the price for that glimpse with his sanity. Like many in era he flew close to the sun paid for it.

Pet Sounds isn’t just one of the greatest pop albums ever made – it’s a document of human consciousness pushed to its absolute limits and somehow managing to create beauty instead of chaos. Wilson took drugs that would have turned most people insane and used them to access musical dimensions that don’t exist for the rest of us. But he could only do this because he’d spent years building the technical and emotional vocabulary necessary to translate the untranslatable.

Now years later, Pet Sounds stands as both monument and warning – proof that sometimes genius requires madness, but also that madness without the foundation of obsessive craft development produces only chaos. Wilson’s achievement was combining systematic musical development with chemical consciousness expansion, creating something that transcended both.

Essential, heartbreaking, still beyond the comprehension of the majority. In era? Conpletely out there.