Nearly half a century after its release to a mixed response from fans and music writers , Wire’s ‘Chairs Missing’ continues to sound like a transmission from the future. While punk’s original fury has long since fossilised into museum pieces, this extraordinary second album remains as sharp, relevant and bewildering as the day it emerged from London’s art-school underground in 1978. No more punk of Pink Flag, synthesisers, atmospheric production and intricate arrangements had the hardcore punks scratching their heads.

What makes an album endure when so many of its contemporaries have faded into historical curiosity? How did four unassuming blokes in sensible jumpers manage to create a blueprint that’s still being copied today? And why does ‘Chairs Missing’ sound more modern than records released last week?

In this retrospective, I explore how Wire’s clinical precision, ruthless economy and gift for subversive melody created something that transcended its punk origins to become one of the most influential albums in rock history. From the metronomic menace of ‘Practice Makes Perfect’ to the gorgeous brevity of ‘Outdoor Miner’, ‘Chairs Missing’ didn’t just predict the future of guitar music – it wrote the instruction manual.

Looking back from our vantage point nearly half a century on, it’s almost impossible to overstate just how thoroughly Wire’s ‘Chairs Missing’ rewrote the rulebook. Released in that feverish summer of ’78 when punk was busy eating itself and disco was conquering the globe, this magnificent second album stands as the moment when four art-school oddities from London quietly laid the foundations for post-punk, alternative rock and about a dozen other genres that didn’t even have names yet.

What’s most striking today is how startlingly modern it still sounds. While the Sex Pistols’ once-revolutionary racket now feels like historical tourism (if you’re interested there is an actual Punk Tour of London), ‘Chairs Missing’ could have been recorded last Thursday. The clinical precision of ‘Practice Makes Perfect’, with its metronomic pulse and Colin Newman’s clipped vocals, created a template that bands are still copying today, whether they know it or not.

Wire’s great trick was ruthless economy. Nothing wasted, everything measured, not an ounce of fat or self-indulgence. When they emerged from the punk scene, they ditched the bondage trousers and safety pins while keeping the urgency and directness. To this unruly mix they added something genuinely new, a cool, analytical intelligence that treated the studio as a sterile surface lab and pop music as an experiment worth conducting properly.

‘I Am The Fly’ still buzzes with menace, Newman’s proclamation that he’s “the fly in the ointment” serving as the perfect manifesto for a band who were always happiest disrupting expectations. They were provocateurs, but never pranksters because there was too much serious intent behind those deadpan expressions.

The album’s great revelation was how Wire embraced melody without sacrificing their edge. ‘Outdoor Miner’ remains one of the most perfectly constructed pop songs of the era, its fabulous hooks and harmonies smuggled in inside a deceptively simple arrangement. At under two minutes, it demonstrated Wire’s other great talent, knowing exactly when to end a song. No three-minute pop formula for this lot, no siree.

‘Heartbeat’, once merely impressive, now sounds positively prophetic, its pulsing electronic textures and detached vocal style laying groundwork for everything from Joy Division to LCD Soundsystem. When Newman asks “How many heartbeats will there be?”, he’s not just confronting mortality but questioning the very mechanics of existentialism heady stuff for a time when most guitar bands were still bellowing about getting pissed or laid, or even being let out at all.

What’s become clearer with each passing decade is how ‘Chairs Missing’ represented a road map for what intelligent guitar music could be, cerebral without being pretentious, experimental without disappearing up its own backside and genuinely challenging without being unlistenable. In their forensic deconstruction of rock conventions, Wire created something far more durable than the three chord thash and bash of contemporaries.

The influence is simply everywhere: from R.E.M. to Radiohead, Elastica and Interpol, even Blur – they all owe some debt to Wire’s clinical brilliance. Even younger bands today, with their angular guitars and oblique lyrics, are still dipping into the well that Wire dug with ‘Chairs Missing’.

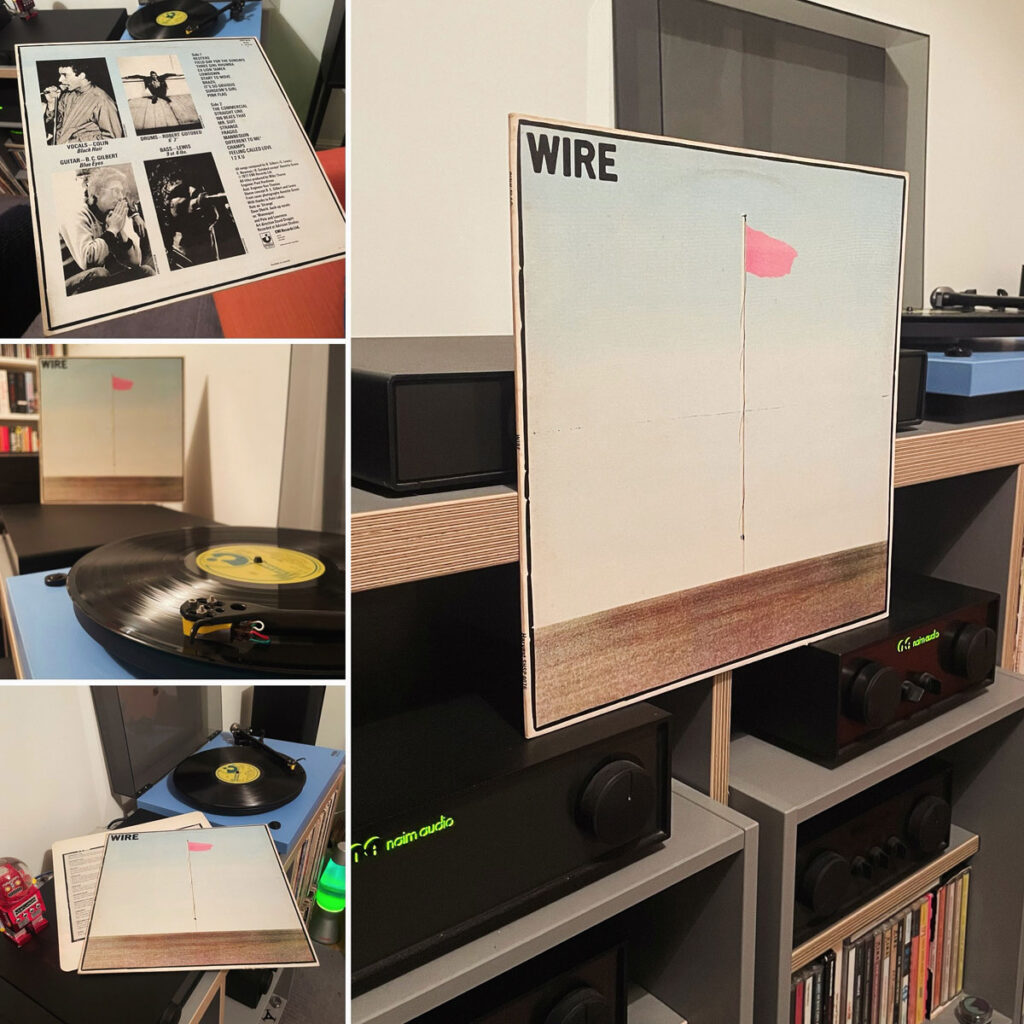

Nearly fifty years on, this remains the sound of a band operating with absolute clarity of purpose, creating music that existed entirely on its own terms whether that was jagged or etherial. While countless landmark albums from the period have aged like milk left out of the fridge, ‘Chairs Missing’ stands pristine and untarnished, still bewildering, still thrilling, still essential and still played.

Not bad for a bunch of art-school refugees who looked like mildly rogue bank clerks – which of course was also relatable to anyone making do outside of the Seditionaries clique.