Forged in a Stretford attic, dismissed by its own singer and dogged by controversy, The Smiths’ debut still changed British music forever. Forty years on, its northern jangle, bitter poetry and doomed legacy sound sharper than ever.

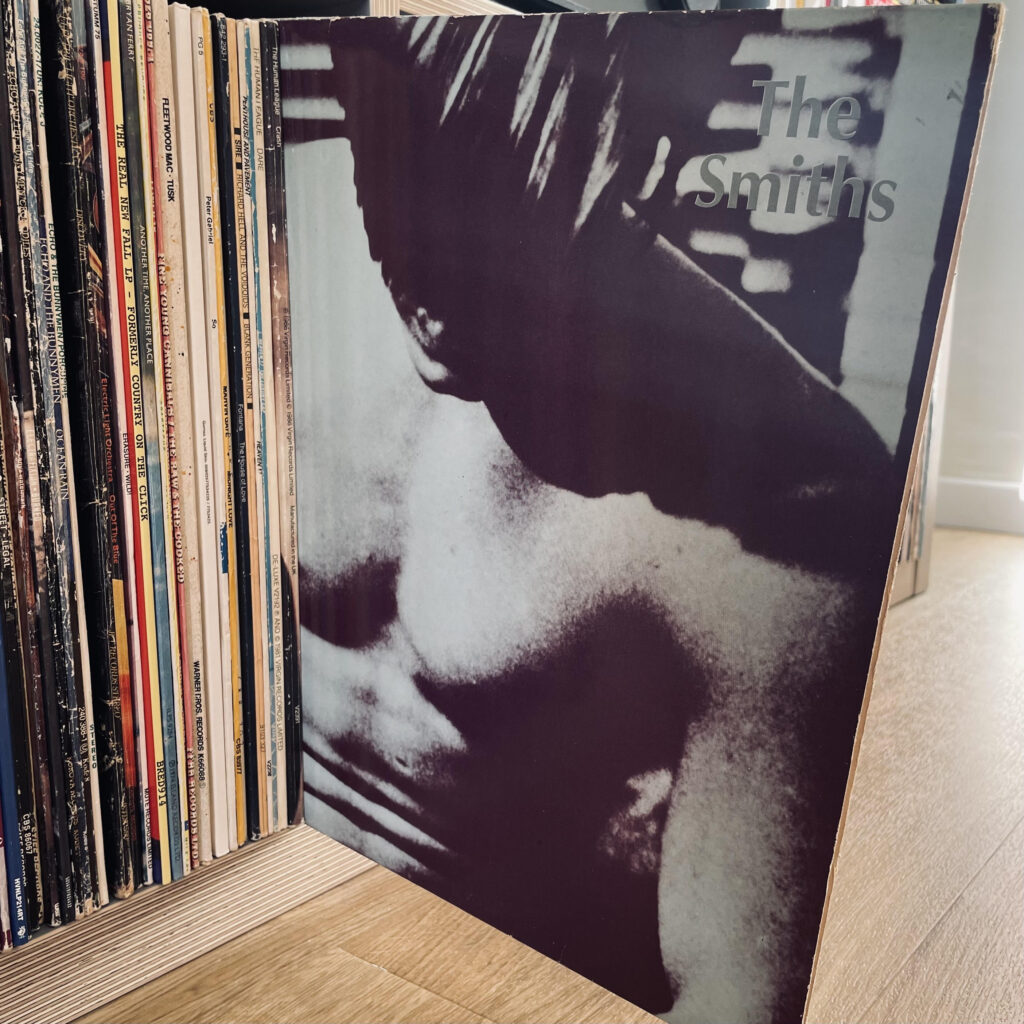

The Smiths – The Smiths (Rough Trade, 1984):

Cast your mind back to February 1984 and the brittle landscape of British pop. The charts are drenched in synthesisers and covered with eyeliner, samples and sequencers are elbowing guitars into the wings. Then, out of the drizzle, four skinny lads of Irish descent from Manchester lurch onto the scene; one clutching gladioli, another his Rickenbacker like a bayonet. They call themselves The Smiths, the most ordinary name imaginable. In that choice alone lies the revolution.

The partnership had begun two years earlier with Johnny Marr knocking on Steven Patrick Morrissey’s door in Stretford a moment Morrissey would later recount in Autobiography with cinematic precision: the “handsome stranger in drainpipe jeans” standing on the doorstep, “smiling with the certainty of someone who knew what was next.” In Marr, he found his melodic twin; in Morrissey, Marr found someone who could give his guitar lines a wounded voice.

They began in Marr’s attic, crafting early songs like “The Hand That Rocks the Cradle” and “Suffer Little Children.” Morrissey later wrote of those first sessions as “a new pulse in the dull heart of the city,” though he would remain forever unsatisfied with how their debut finally sounded.

The road to that debut LP was fraught. Morrissey recalled how Rough Trade, “a label without the cash or the courage to lead,” seemed both ally and obstacle. The Troy Tate produced sessions at Elephant Studios collapsed under the heat, guitars going out of tune, tempers fraying. John Porter re-recorded the lot. Morrissey, ever the perfectionist, declared the results “not good enough,” but at a cost of £6,000 Rough Trade said it would have to do.

So The Smiths* emerged: flawed, magnificent, defiantly northern.

It opens with “Reel Around the Fountain” a slow, aching waltz of shame and seduction. Marr’s guitar drips like rain from the rooftops, Rourke’s bass curls around it, and Morrissey sighs, “It’s time the tale were told…” From the first line, it’s less an album and more a confession.

Then comes “You’ve Got Everything Now”, sharp and bitter, a howl from the uninvited. “Miserable Lie” follows, schizophrenic and breathless – part lullaby, part nervous breakdown. And then “Pretty Girls Make Graves”, all glittering guitars and doomed romance, Morrissey cutting through the post-punk fog with a sneer and a sigh.

Side two delivers the anthems that defined the band. “Still Ill”, with its tremulous jangle and weary poetry, reads like Morrissey’s entire philosophy in three minutes “Does the body rule the mind or the mind rule the body? I dunno…” Then “Hand in Glove”, the debut single that started it all, a clattering burst of urgency with the immortal claim that “the sun shines out of our behinds.” It was ludicrous, brazen, brilliant – the ultimate outsider song.

“What Difference Does It Make?” gave them their first true hit, a bruised pop song with its teeth showing, while “I Don’t Owe You Anything” slows the pulse, Paul Carrack’s organ sighing under Morrissey’s rejected torch-song croon. And closing the record, the infamous “Suffer Little Children” the Moors murders rendered as gothic lullaby. Morrissey later wrote that he “could not sing it without shivering,” but Ann West, mother of victim Lesley Ann Downey, came to see it for what it was: sorrow, not exploitation.

The album hit number two, a trend that would follow them around – blocked from the top spot by Simple Minds’ attempt at stadium rock ‘Sparkle In The Rain’. The reviews were split. NME’s Don Watson sniffed at the “lacklustre sound,” calling it “a death of the punk ideal.” Others called it genius. Critic Dave DiMartino said he hadn’t “been as fascinated by an album in years.” Morrissey, impervious as ever, proclaimed it “a signpost in the history of popular music.”

He wasn’t wrong.

In Autobiography, Morrissey remembers the aftermath with mingled pride and exasperation – a record born “out of nothing but belief” yet betrayed by “the poverty of studio time.” That tension is what keeps The Smiths alive. The imperfections are its pulse.

By 1987 the band had imploded, Marr walking away, Morrissey wallowing in resentment. The nineties brought lawsuits and character assassinations that were hard to shrug off. Mike Joyce suing for unpaid royalties and winning, the courtroom exchange finishing off whatever friendship remained. Marr and Morrissey never reconciled, and when Andy Rourke died in 2023 after a long illness, the final curtain fell. The reunion everyone wanted, the one they both secretly feared was gone forever. A relief no doubt.

So this debut remains a flawed masterpiece built on attic dreams, frustration and northern defiance. From “Reel Around the Fountain” to “Suffer Little Children”, from “Still Ill” to “Hand in Glove”, it a rain-streaked declaration that ordinary lives could sound extraordinary.

Born in drizzle and doubt, it still shines like broken glass under the streetlights of Manchester.