Today marks the 45th anniversary of London Calling, The Clash’s groundbreaking double album that redefined punk and reshaped British music. More than just a record, it was a bold statement, mixing genres, politics and raw emotion with a restless energy that still resonates. In this definitive retrospective, I delve into the album’s iconic sleeve, the sprawling diversity of its songs, and the pivotal role played by producer Guy Stevens in crafting a sound both urgent and timeless.

By the winter of nineteen seventy nine The Clash were standing at a crossroads that most bands never reach. Punk had given them a voice and a platform, but it was already clear that the narrow version of the movement being sold back to the public would not hold them. London Calling arrived not as a rejection of punk but as an argument with it. An artful double album crammed into a single sleeve, a density made up of ideas and restless energy, it sounded like a band refusing to be boxed in by its own reputation. This was The Clash insisting that urgency did not have to mean limitation, and that rebellion could be rhythmic, melodic and historically aware all at once.

“London Calling is the first of The Clash’s albums that is truly equal in stature to their legend”. Charles Shaar Murray NME 1979.

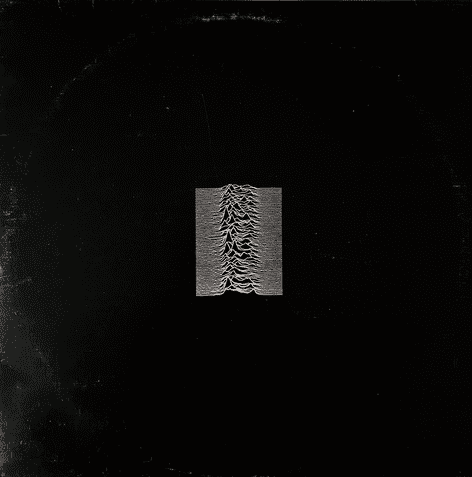

The sleeve announced that intent before a note was heard. Pennie Smith’s photograph of Paul Simonon mid swing, bass guitar raised and about to be smashed against the stage floor at the Palladium in New York, is still one of the defining images of British music. It is beautifully blurred, caught in motion rather than reverence. Overlaid with the pink and green lettering lifted from Elvis Presley’s debut album, it made a knowing claim on rock and roll history while quietly asserting ownership of it. The decision to house the double vinyl in a single sleeve was driven by CBS insistence the album was a single album but relented to the inclusion of a 12 inch single. Artfully the band added the further nine tracks to the extra vinyl and flipped the 45rpm to 33rpm – the finished ‘double’ album complimented by a “Pay No More Than” hype sticker. So no gatefold excess, the lyrics were printed on the inner sleeves, practical and open, inviting the listener to engage with the words as part of the experience rather than as an accessory.

Musically the record sprawls, but it never drifts. The title track opens like an emergency broadcast, Strummer’s voice riding a sinewy rhythm as images of nuclear anxiety, flooding and social collapse tumble out with the urgency of a last transmission. From there the album refuses to settle into any single identity. Brand New Cadillac barrels through rockabilly with reckless joy. Jimmy Jazz slouches through smoky shadows. Rudie Can’t Fail lifts the mood with warmth and swing, its horns and skank rhythm sounding like celebration as defiance.

What becomes clear as the sides unfold is that this breadth is not a stunt. These styles were absorbed, argued over and lived with. The historically underrated Mick Jones brings melody and pop intelligence, shaping songs that are generous and emotionally direct. One of the album’s most cherished moments, Train in Vain, sits at the very end of Side Four and was a late addition, originally intended to be given away as a free flexi-disc with NME before that plan fell through. The band insisted it be included on the album, but because the sleeves were already printed it was not listed on the cover or lyric sheets and initially appeared as a surprise hidden track etched into the run-off groove. Its immediacy and vulnerability, sung by Jones, with a narrative of love lost, feel like the intimate counterpoint to the political breadth that precedes it.

Joe Strummer’s writing elsewhere on the record grows more impressionistic and humane, trading blunt slogans for scenes, doubts and contradictions. Paul Simonon’s bass is central to the record’s physical pull, and his vocal turn on Guns of Brixton adds a colder, more controlled shade to the palette. Built on a taut reggae rhythm, the song’s sense of unease and inevitability reflects the lived tensions of South London without theatrical exaggeration. “When they knock on your front door, how you gonna come? With your hands on your head or on the trigger of your gun.” – now that is Thatcher’s London Punk ‘1979 style’.

The deeper cuts are where London Calling truly reveals its confidence. Koka Kola disguises its critique of creeping Americanisation beneath a jaunty shuffle, its irony sharpened by how pleasant it sounds. Spanish Bombs is one of Strummer’s finest lyrics, fragmented and poetic, its half-remembered Spanish phrases and images of civil war and tourism colliding into a meditation on distance, memory and solidarity. The Four Horsemen lurches forward with apocalyptic humour, biblical imagery delivered with a grin that barely masks the anxiety beneath. Death or Glory pairs one of Jones’s most immediate melodies with a lyric that quietly punctures the romance of rebellion itself.

Even the stylistic detours serve a purpose. Lover’s Rock leans into reggae’s sensuality without losing tension. Wrong ’Em Boyo tips its hat to ska’s roots with genuine affection, not as nostalgia but as acknowledgement. Each track adds another voice, another rhythm, sketching a map of London as a listening city where cultures collide and converse.

Holding this sprawl together was producer Guy Stevens, a volatile and divisive presence whose background proved crucial. Stevens came from an earlier era, steeped in rhythm and blues and shaped by his work with Mott the Hoople. He believed in feel above all else. Precision bored him. Commitment did not. His behaviour in the studio has become part of the album’s mythology, but beneath the chaos was a clear philosophy. Stevens pushed the band to play as if the songs might fall apart at any moment, to reach for performances that felt dangerous rather than correct.

That approach suits London Calling perfectly. The record breathes. Tempos flex. Instruments bleed into one another. There is space in the sound, even at its densest, and a looseness that gives tracks like Clampdown and Guns of Brixton their physical weight. The tension between band and producer was real, but it was productive, forcing instinct to override caution.

As a production, the album strikes a rare balance. It sounds expansive without being bloated, raw without being thin. The double album format could easily have sunk it, but instead it allows the band to pace the journey, each side carrying its own momentum and mood. By the time Train in Vain fades out, there is a sense of having travelled not just through styles, but through arguments, fears and affirmations.

Decades on, London Calling remains a challenge as much as a classic. It asks whether a band can grow without losing its edge, whether politics and pleasure can coexist, whether history can be acknowledged without becoming a trap. The sleeve still feels perfect. The songs still feel urgent. Guy Stevens’s restless spirit still hums through the grooves. The Clash did not simply make a great double album. They made a statement of intent that continues to sound alive, unresolved and necessary.