The Artistic Bond Between Ian Dury and Peter Blake.

In the vibrant landscape of post-war British art and music, few creative partnerships have been as meaningful yet understated as the one between punk & new wave pioneer Ian Dury and pop art master Sir Peter Blake. Their collaboration bridged the worlds of fine art and popular music, creating a visual and sonic language that celebrated British culture in absolute eccentric glory.

The foundation of their relationship was built at the Royal College of Art in London, where Blake taught in the painting school during the early 1960s. Among his students was a young Ian Dury, who enrolled to study painting before his musical career took flight. This teacher-student relationship evolved into a friendship and creative partnership that would span decades.

Blake, already known for his pop art style and collage techniques, recognised in Dury a kindred spirit who appreciated the beauty in everyday British imagery and vernacular. Both artists shared an affection for music hall traditions, seaside entertainment, and the rich tapestry of working-class British life.

Their most famous collaboration came in 1977 when Blake designed the iconic cover for Dury’s album “New Boots and Panties!!” with his band The Blockheads. The cover featured Dury and his son Baxter standing outside a clothing shop in London’s East End, capturing the authenticity and unpretentious quality that characterized both artists’ work.

This wasn’t Blake’s first venture into album artwork, he had already created the legendary collage for The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” a decade earlier. However, his work with Dury reflected a different sensibility: less psychedelic fantasia and more urban realism, though both shared a deep appreciation for cultural references and visual richness.

The visual aesthetic Blake helped create for Dury became part of the artist’s signature style, combining elements of music hall, fairground art, and British seaside postcards with the energy of punk. This visual language perfectly complemented Dury’s lyrics, which celebrated similar themes with linguistic dexterity and wit.

What bound Blake and Dury together was more than just a professional relationship, it was a shared artistic philosophy, a Pop Art manifesto:

Democratic Art – Both believed in art that spoke to ordinary people without condescension. Blake’s pop art embraced everyday imagery and commercial design, while Dury’s music combined highbrow wordplay with the rhythms and language of the street.

British Cultural Heritage – They shared a deep appreciation for distinctly British forms of entertainment and expression from music hall traditions to seaside amusements, fairgrounds, and the rich lexicon of Cockney rhyming slang.

Visual Storytelling – Both artists were masterful visual storytellers. Blake through his intricate collages and paintings, Dury through his character-driven narratives and vivid lyrical portraits.

Authenticity – Neither artist was interested in pretension. Blake’s work celebrated real people and places, while Dury’s songs gave voice to characters often overlooked in popular music.

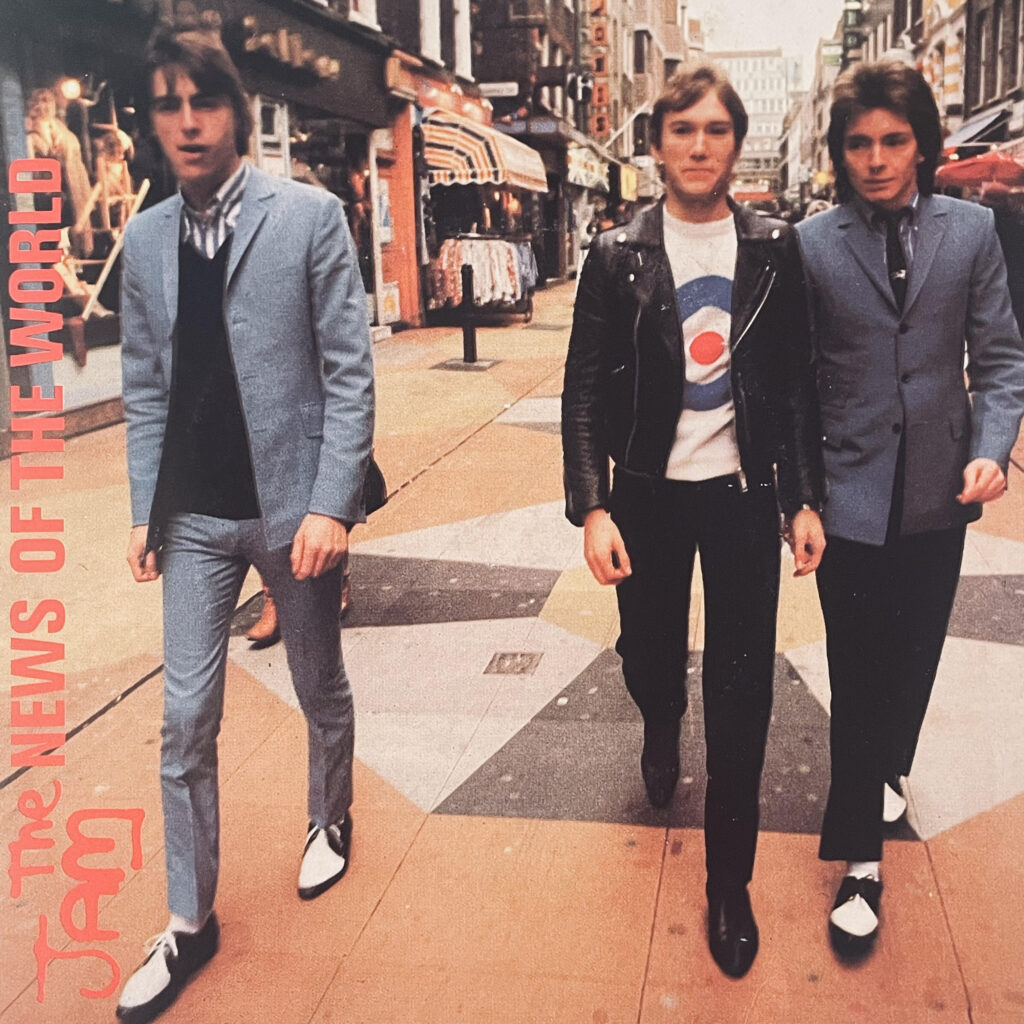

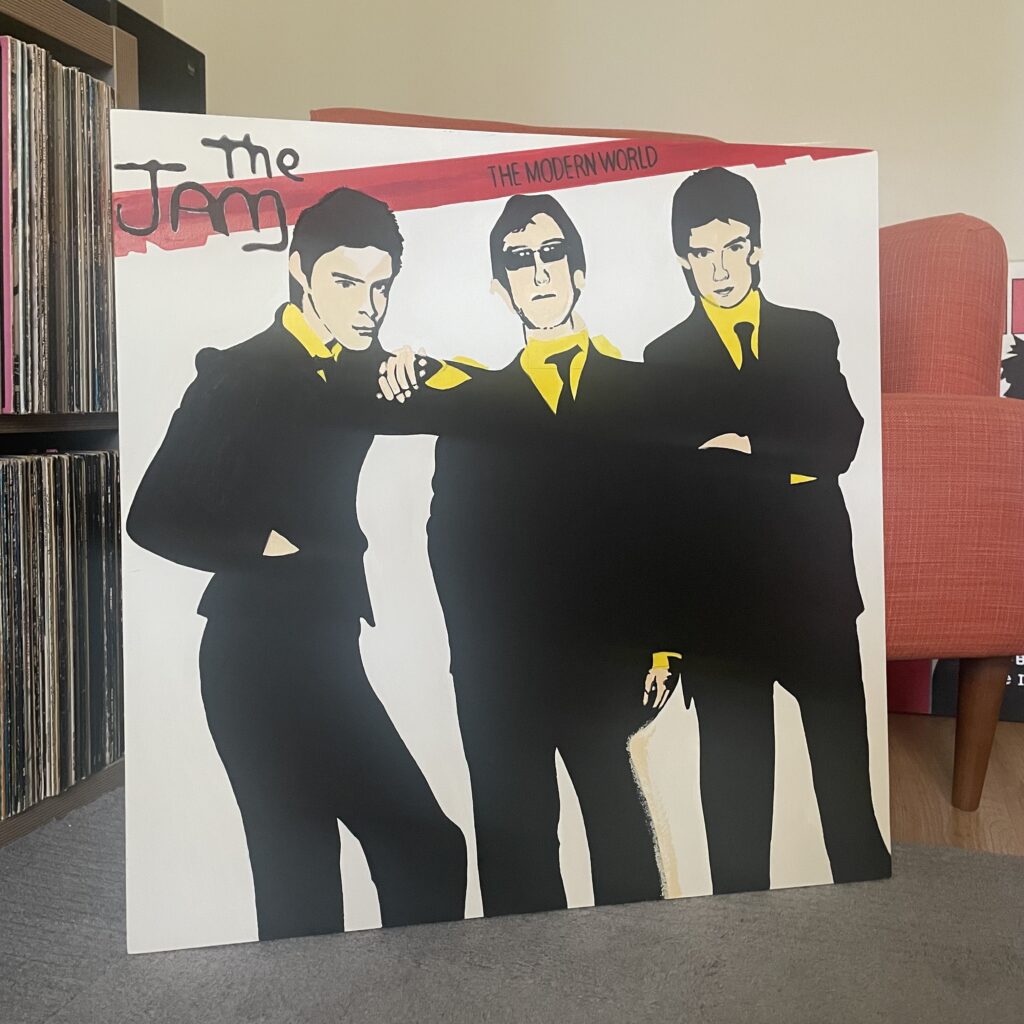

The visual language they developed together helped define Dury’s public persona as an artist deeply rooted in British tradition yet thoroughly modern in his sensibilities. Blake, for his part, continued to be inspired by music throughout his career. Having worked with Dury, he went on to create artwork for other British musicians, including Paul Weller, Oasis, and The Who. His experience collaborating with Dury undoubtedly informed these later musical partnerships. Ian Dury’s painting style very similar to Blake’s, in fact they could be confused.

The Blake-Dury collaboration represents an important moment in British cultural history, a time when the boundaries between “high” and “low” art were being deliberately blurred, and when artists were reclaiming and celebrating aspects of British culture that had been previously dismissed as vulgar or trivial. Evidenced in the 1962 BBC TV episode of ‘Monitor’ a previously establishment series reserved for fine art and classical music sensibilities showing a laid back, montage style documentary by Ken Russell dedicated to pioneering Pop Artists; Peter Blake, Derek Boshier, Pauline Boty & Peter Philips. These occasional media break outs preparing the ground for later.

Their partnership demonstrated how visual art and music could reinforce and elevate each other. Blake’s artwork didn’t simply influence Dury’s music it contextualised it, providing literary-visual pop art inspired cues that enhanced the listener’s understanding of the musical content. For me, the Blake-Dury relationship is the epitome of Pop Art and Art Pop, Blake’s influence was so essential to Dury I don’t believe he would have existed or been anywhere near as popular without. In perspective, the surprising statistic that Dury was the U.K.’s biggest selling pop artist in 1978.

Today, their collaboration stands as a testament to the power of cross-disciplinary artistic partnerships. The visual language they developed together continues to influence album artwork and the presentation of musical personas, while their shared appreciation for the vernacular aspects of British culture has helped shape subsequent generations of British artists and musicians.

In a cultural landscape increasingly dominated by global influences, the Blake-Dury partnership reminds us of the rich creative potential that can emerge from deeply local inspirations proving that the most universal art often comes from the most specific cultural contexts.

Their legacy lives on in their shared vision of an art that speaks to and celebrates the lives, language, and experiences of ordinary people an artistic philosophy as relevant today as it was when a young Ian Dury first sat in Peter Blake’s classroom at the Royal College of Art.

Ian Dury Royal College of Art, 1964-1967.

—

Art Pop / Pop Art: a study of the influences of art school, famous artists and movements on pop and rock music. Those institutions where failure is motivation, where the eccentric and pretentious emerge into the fascinating space where art and music meet.