A retrospective review of Dire Straits’ 1980 album Making Movies. Knopfler’s technical brilliance meets romantic melancholy in an era that supposedly had no use for either. In my heavily late Seventies NME hack influenced style.

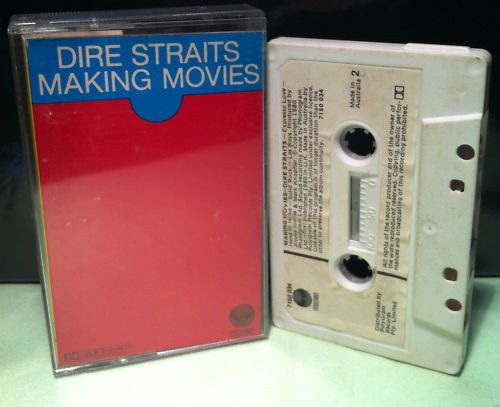

DIRE STRAITS: Making Movies (Vertigo) 1980

There was something deeply suspicious about a band this technically accomplished in 1980. While half of London was still thrashing about in bin liners and safety pins, Mark Knopfler’s lot turned up with an album so pristine, 38 minutes so meticulously crafted, that you half expected to find the corners mitred.

Making Movies arrived eighteen months after their self-titled debut made them improbable millionaires in America, and it was clear they’d been spending the intervening period in expensive studios rather than the back rooms of grotty pubs. Recorded at New York’s Power Station with Jimmy Iovine producing – the man who’d just finished polishing Springsteen’s The River – this was Dire Straits going for broke, or rather, going for more money than they’d already got.

The opening salvo, “Tunnel of Love,” sprawled across eight minutes like some Dylanesque fever dream filtered through a Tyneside accent. It was all fairgrounds and Spanish guitars, with Knopfler’s finger-picked lines circling each other like moths round a sodium lamp. The man played like he was being paid by the note, which he probably was.

“Romeo and Juliet” – which got played to death on Radio 1 – was the sort of thing that had sixth-formers scribbling lyrics in the back of their French textbooks for years. It was wretchedly romantic, all unrequited longing and cinema queues, with Knopfler doing his best to sound like he’d actually had his heart broken rather than just read about it in a Leonard Cohen novel.

But here was the rub: it worked. Despite themselves, despite the almost offensive levels of musicianship on display, despite the fact that punk never happened in their world, Dire Straits crafted something genuinely affecting. “Hand in Hand” swung like prime-era Dylan, while “Les Boys” – a tawdry tale of Parisian transvestites – had the sort of seediness that Bowie used to do before he discovered Switzerland and synthos.

The centrepiece, though, was “Skateaway,” a peculiar bit of New Wave-ish funk about a rollerskating girl cruising through urban decay. It had synthesizers, for God’s sake. Synthesizers! On a Dire Straits record! Pick Withers’ drumming was tighter than a gnat’s chuff, and the whole thing sounded like what might happen if Steely Dan decided to have a go at writing a hit single.

Mark Knopfler remained an enigma wrapped in a headband. His vocals sounded like he was perpetually on the verge of nodding off, yet there was a sly intelligence to his wordplay that elevated this above standard-issue soft rock tedium. He’d clearly listened to a lot of JJ Cale, a lot of Dylan, a lot of those American FM radio staples, and he wasn’t afraid to nick the best bits.

The production was, predictably, immaculate. Every hi-hat shimmer, every bass throb from John Illsley, every keyboard wash from Roy Bittan (on loan from the E Street Band, no less) sat exactly where it should. It was the sonic equivalent of a freshly Hoovered front room with the cushions all plumped up.

Which brought us back to that initial suspicion. In an era when the most exciting music was being made by people who could barely play their instruments, Dire Straits were almost confrontationally competent. They weren’t interested in year zero, in tearing it all down and starting again. They wanted to take you to the pictures, buy you chips on the way home, and maybe have a bit of a cuddle if you were lucky.

And you know what? Sometimes that was enough. Making Movies didn’t change your life or inspire you to form a band in your mate’s garage. But on a rainy Tuesday evening when you were skint and miserable and the world seemed determined to grind you down, it might just have made things seem temporarily bearable.

Which, in 1980, was worth something.